Chapter 11. Application

Chapter 11 doesn’t explain in detail over 20 years of my work on projects in various countries because many other people were necessarily drawn into the vision and they made their own significant and dedicated contribution. Projects continue and expand in Australia, Africa, South Asia, and East Asia. Click here to look at projects undertaken by Health Communication Resources and Amplifying Voices.

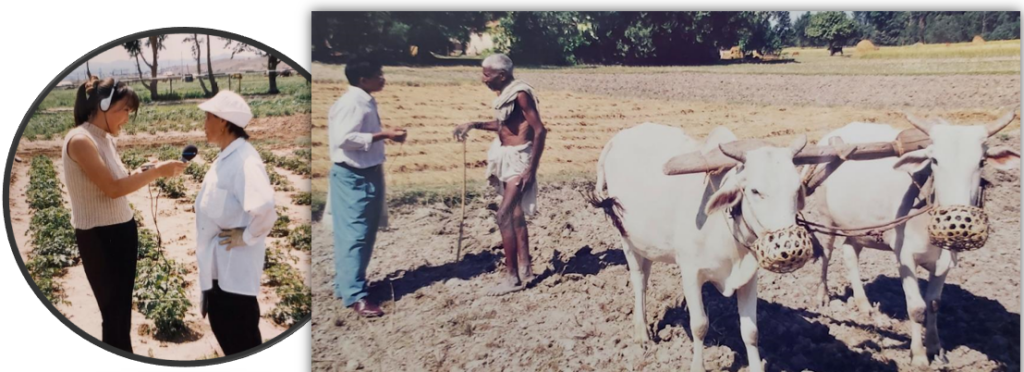

‘Getting your feet dirty’ and the ‘ting thing’ was a key strategy to apply in Mongolia, Mindanao, Pakistan, Indonesia and elsewhere.

Training volunteers to interview people from their communities and to prepare radio scripts on topics relevant to their communities was another key strategy.

Before digital technology made film in cameras redundant, photograph prints could be enlarged or “blown up”. The notification for this Kodak film store service was rather awkwardly displayed on a street in Cotabato, Mindanao, where nearby bombings and shootings were common.

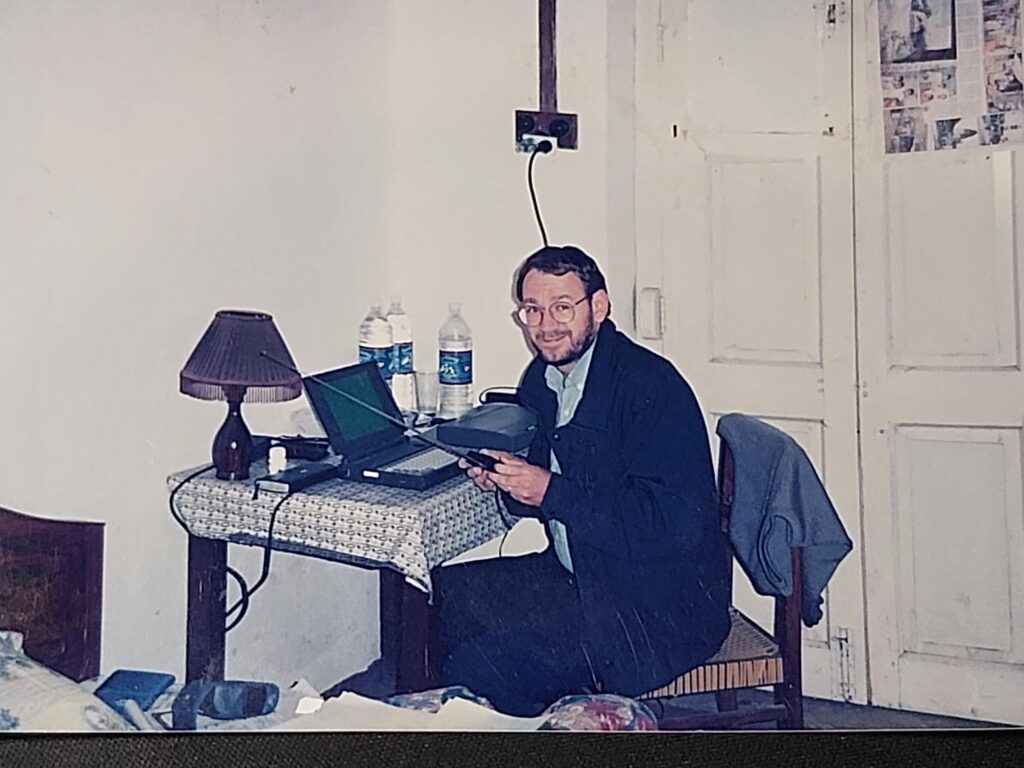

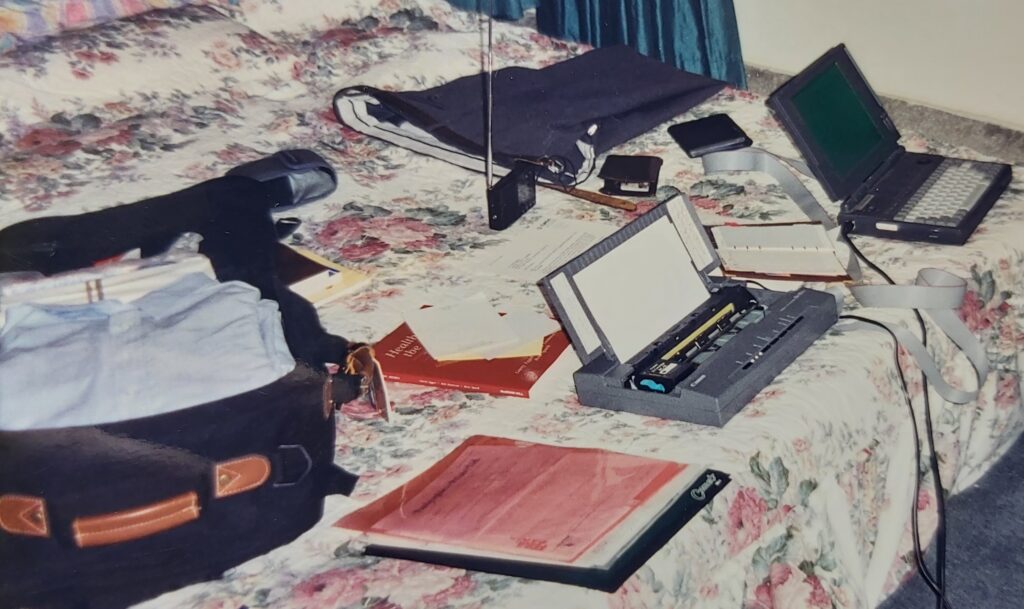

For many years two shirts, two pairs of trousers, three pairs of socks and underwear, toothbrush and toothpaste, laptop, portable printer, mini-shortwave radio receiver, camera, diary, a Bible and a couple of books fitted into a carry-on bag for flights, and my office a hotel room bed.

The indefatigable Frank Gray: broadcast visionary, pioneer, and designer of the Gray Matrix. Proud to have been a colleague.

Bits that didn’t make it into the book

First trip to Mongolia

It was very exciting to be a part of the establishment of the WIND FM initiative. I travelled there a number of times, sometimes twice in a year. In just a few years, WIND became recognised by the government of Mongolia for its high standards of programming. My task was to provide a programming strategy to bring about social change based on human needs, and provide the tools and training to do that. The first trip started with a day swimming at a beach in Perth with Jill in 38oC heat. Twenty-two hours later I was sitting in a downtown restaurant in Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia with Batjargal, the Director of WIND FM. On the footpath, just a metre beyond the glass window, people walk by in the -8oC temperature, rugged up in thick fur coats and hats. It is so cold the parked cars have protective blankets stretched over the bonnet to maintain the engine’s warmth and prevent oil and diesel turning to sludge. Later, I walked along the iced-covered footpath to my hotel, tips of my ears, and chin and lips aching with cold. Standing at my hotel window, now snug and warm, I watched a young man enter his accommodation. He pulled back a manhole on the street, slid inside, and pulled the metal covering back across the hole. Batjargal explained to me the next day that hot water from the city’s power station is dispersed through large pipes to thaw ice on the streets and circulated through heating systems in the city’s Soviet-era communal apartments. Homeless people, families even, live under the streets this way to keep warm. I don’t know how they survived.

Vis a vis visa

My travel agent had told me I could get a visa upon arrival in Mongolia, but on departure at Perth airport the airline wouldn’t let me on the plane, because I didn’t have a letter of invitation from a local Mongolian organisation. The airline decided to let me take the first leg of the flight to Singapore, but I wouldn’t be able to continue if I couldn’t show a letter to the airline in Singapore. In the 5 hours of my flight to Singapore, Jill, in her usual unflappable way, pulled it off. She rang people in England to get contact details of people in Mongolia that we didn’t have. Her phone call to Mongolia resulted in a letter faxed from Mongolia to Jill who faxed it to the airline at Changi Airport in Singapore, just in time for my arrival there.

It’s the people you remember

People who trained at WIND FM would sometimes go to other jobs, but they took their new-found skills and became an influence elsewhere. One of those people was Aiyuka, greatly valued at the radio station for his technical competence and ethical and spiritual values. But, he felt obligated to accept a personal request from the governor of his home province to take up an important position: to investigate complaints against local police, government officials and businesses, as well as to authorise and validate various applications and licences. For example, he had to validate claims by students that they were from a poor family and were eligible for a government education scholarship. Very soon he was offered bribes, one being a month’s salary to illegally validate a building application. Aiyuka had taken up the position during a period when I wasn’t in Mongolia, but he travelled 400 kms to see me, when he heard I was back for a visit, to make sure I understood his motives. He said he felt obligated to give something back because he’d learned so much in his training, and his home province was socially and economically disenfranchised: electricity had only arrived in the capital of the province (population 5,000) the previous year, five out of 10 men had no job, and alcoholism and domestic violence was rife.